What first drew my attention was the figure. A Black woman, with layers of blue beneath her skin, poised, elegant, bearing a crown. She is an embodiment of Black Southern defiant dignity. Our mothers and grandmothers, the women who cooked and cleaned and labored in fields, were treated as inferior, yet they still bore themselves with endless grace and modeled it for us. Before I knew much about the artist, Amy Sherald, I knew the intimate story she was telling.

What first drew my attention was the figure. A Black woman, with layers of blue beneath her skin, poised, elegant, bearing a crown. She is an embodiment of Black Southern defiant dignity. Our mothers and grandmothers, the women who cooked and cleaned and labored in fields, were treated as inferior, yet they still bore themselves with endless grace and modeled it for us. Before I knew much about the artist, Amy Sherald, I knew the intimate story she was telling.

I’d heard of her, however, through friends. Sherald had painted someone I knew. I’d heard she attended an art school with which I was very familiar through family. She had a reputation for excellence, but my encounter with her work was more than simple admiration. It was complete captivation. I felt I had to have a piece by her, and I wanted this one in particular. That said, I was hardly in a position to begin collecting art. My budget was tight, my responsibilities to others were high. But I shyly approached Sherald about purchasing the piece over time. Her generosity was heart-warming and frankly life changing. It was the first significant piece of art I ever owned.

I learned the title of the piece was Welfare Queen. It was a term that circulated quite frequently in the 1980s. Back then it was used to conjure up images of Black women who were seen as lazy, feeding off the state, bearing children irresponsibly, and just generally acting as a burden on society. Political speeches, news reports, and everyday chatter talked about the problem of “Welfare Queens.”

There was a woman, Linda Taylor, whose unusual story of collecting welfare checks in multiple states became a public warning. And despite the fact that Black women were excluded from the welfare state benefits for the first decades of the program, public assistance had come to be negatively associated with Black women. It haunted us. How could this be our image in the public, Black women who we knew almost universally worked endlessly to make something out of nothing?

We saw our mothers and grandmothers toil and serve. But the world apparently didn’t.

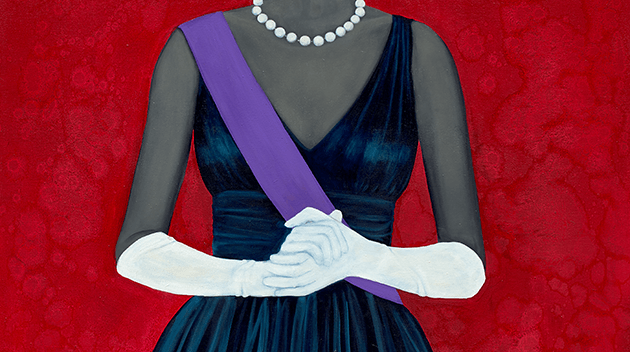

Thank goodness for Black women’s literature of that period. It told a much different story than what we heard in public. I devoured books by women such as Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara, and Paule Marshall. And I mention that here because the feeling of looking at this “Welfare Queen” painting, many years later, was akin to opening up the world of those books for me. Inside those pages, the fullness of character and creativity among Black women, including poor Black women, was revealed. Likewise, this painting is masterful in revealing so much inside the layers. This “welfare queen” is a beauty queen, adorned in white gloves, bejeweled, bearing a sash that announces her regality. Look to the background, for example. It is a red tapestry, a marvelous contrast and context to the elegant figure with her blue-black skin and golden crown. Her face is placid, yet the brushstrokes remind you that still waters run deep. Her skin matters. In American society, dark skinned women are deemed less beautiful and less valuable. And yet, just as Sherald turned the welfare queen stereotype on its head with a dignified depiction, she has transformed the popular negative meanings applied to deep dark skin. It is not flat nor is it unattractive. Here, it is enchanting.

What at first glance appears to be a simple composition, has a remarkable complexity. Through the days and through the seasons, as the light shifted, and our lives changed, this painting was an endless discovery: new patterns, distinct brushstrokes, a realization of how the nuance of the figure’s body strikes differently based on where you are standing. Welfare Queen was the centerpiece of our home as my sons came of age. We looked at it when feeling joy and when we were in tears. It anchored our own pursuit of dignity and grace when life was most challenging. I wasn’t surprised in the least when first lady Obama selected Amy Sherald as her portraitist. The intelligence of Sherald’s work is magnificent, as is its beauty. I must admit, it is difficult to part with Welfare Queen. It was my companion through writing four books, and a direct inspiration for my next: South to America: A Journey Below the Mason Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation. I literally faced it as I typed through many nights.

But now, it is my hope that the next owner will share my sense of duty in acting as a good steward of the painting. I sincerely believe that it ought to be in the possession of someone who has both the means and sensibility to ensure that it will be protected in the long term, and available when appropriate to the public. I did not grow up in a home with original artwork, but I had the good fortune of having parents who took me to museums constantly. I loved the magic of discovery that happened in museums. When looking at Welfare Queen, I have often imagined what it would have been like to be 8 years old standing before it. I know it would have made my heart swell and tears spring to my eyes, because it still does so today.