Baltimore nurse practitioner Rebecca Coppola cobbled together disability pay, accrued sick days and five paid days off from her employer in order to spend the 12 weeks at home she felt she needed to adequately care for her first newborn.

Although the money she accumulated was helpful, Coppola said she only received 20% of her regular salary over the 12 weeks she was off.

“It’s not enough,” she said.

Without her husband’s salary as a software consultant, the time off would have been even more financially difficult. Even for her husband, it all came with a cost.

“He wasn’t really able to take time to just slow down and focus on bonding as a family,” she said.

Some Maryland Democratic lawmakers in the General Assembly say residents who need paid time off for parental leave, care of a sick family member or for their own health should not have to go through a similar process.

So, they are resurrecting paid family and medical leave legislation that has failed in the previous three legislative sessions with hopes to finally turn it into law.

A coalition of Democratic legislators in the House and Senate introduced bills to give workers up to 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition or disability. It would also cover families with newborn children and those with a need arising out of a family member’s military deployment.

Del. C.T. Wilson, D-Charles, is sponsoring one of the bills, HB496, and Del. Kriselda Valderrama, D-Prince George’s, has introduced similar legislation (HB8/SB275) which was cross filed in the Senate by Sen. Antonio Hayes, D-Baltimore. Lawmakers are unclear when and which bills might receive a vote in the House Economic Matters Committee, which Wilson chairs, and then face full consideration on the House floor.

Late Wednesday, Senate President Bill Ferguson siad he and Maryland Senate Democrats will hold a press conference Thursday to announce their commitment to pass paid family and medical leave legislation at a press conference.

The legislators say a law is needed to protect workers who deal with family challenges so they don’t lose all their income or their job. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, fewer than one in four (23%) workers have access to paid family and medical leave.

Workers and their families lose $22.5 billion in wages each year due to a lack of access to paid leave, and two-thirds of workers who received partial or no pay while on leave struggled making ends meet, according to a Center for American Progress 2021 report.

The Time to Care Act of 2019 failed to make it out of committee. In the 2020 legislative session, a paid family and medical leave bill was introduced, but, like many other pieces of legislation, it was discarded as the General Assembly focused on the burgeoning coronavirus pandemic. Last year, the Time to Care Act of 2021 also died in committee.

Supporters say this year there are signs the legislation could become law, despite past failures.

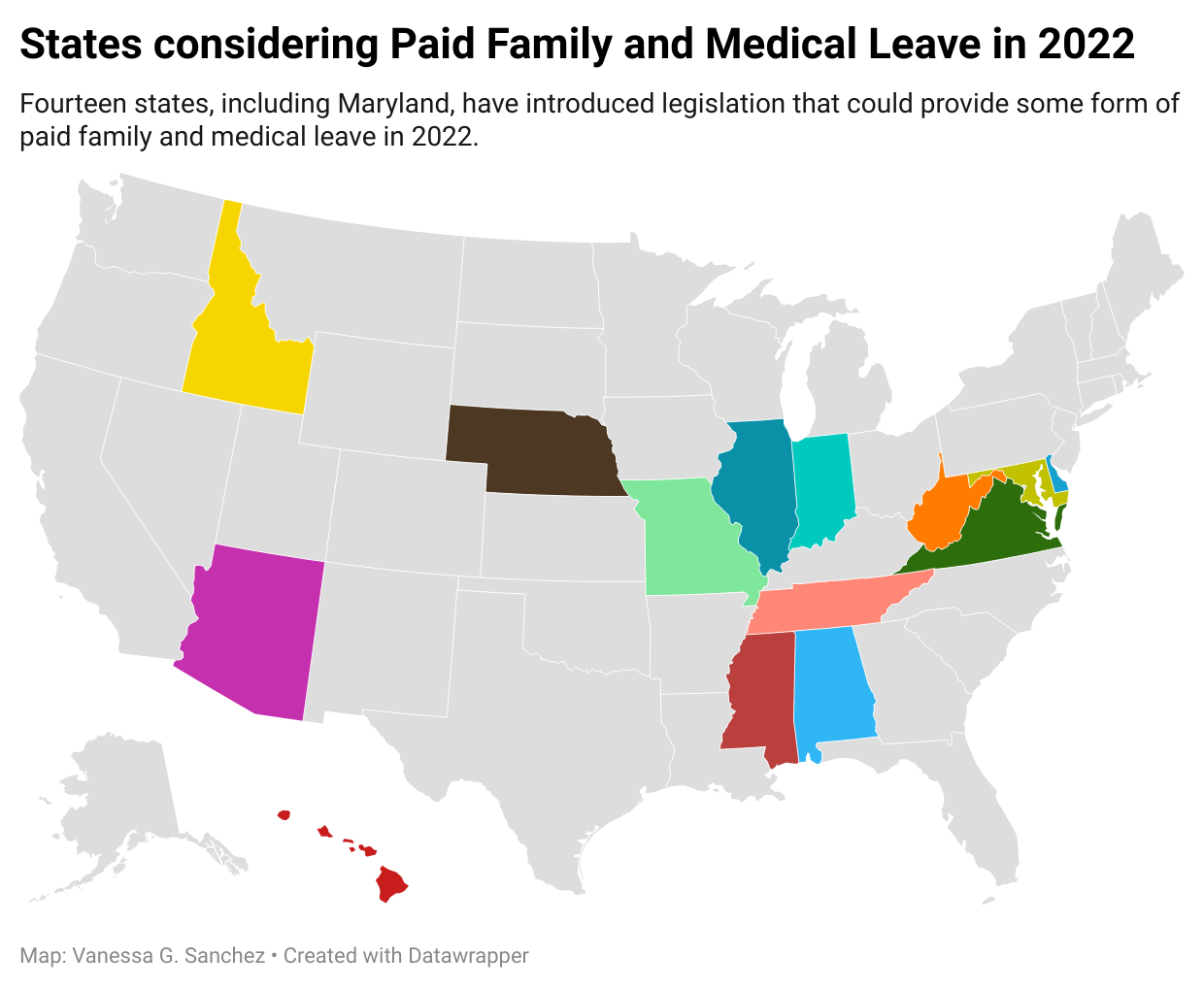

Polls continue to show Americans want it. An October-November 2021 Morning Consult/Politico poll shows that 70% of registered voters strongly (37%) or somewhat (33%) support paid family and medical leave for new parents. Meanwhile, nine states and the District of Columbia have adopted paid family leave legislation in the last decade. Oregon and Colorado’s paid family leave laws are scheduled to go into effect in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Similar legislation is being considered this year by lawmakers in 13 other states, including neighboring Virginia and Delaware.

Meanwhile, nine states and the District of Columbia have adopted paid family leave legislation in the last decade. Oregon and Colorado’s paid family leave laws are scheduled to go into effect in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Similar legislation is being considered this year by lawmakers in 13 other states, including neighboring Virginia and Delaware.

While some workers, like Coppola, can use savings, a spouse’s income, vacation days or personal sick leave to help them through time off, others have no financial cushion, advocates and the bills’ sponsors noted.

Rebecca Coppola and husband John Becher, with their daughters Sage Coppola Becher and Clio Coppola Becher outside their Baltimore row house. Coppola said she cobbled together disability pay, paid sick leave and paid days off to supplement the 12 weeks she cared for her first newborn in 2020. Still, she said, it was a fraction of what she earns in her job. (Joe Ryan/Capital News Service)

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act protects employees’ jobs for up to 12 weeks when they are out, but it does not supply financial support and only applies to businesses with more than 50 employees and public employers.

Under Wilson’s bill, part-time and full-time employees who have worked 680 hours over a 12-month period would be able to receive 12 weeks of pay. They would be eligible for between $50 and $1,000 a week, depending on the worker’s average weekly salary.

To pay workers, the measure proposes a financial pool named the Family and Medical Leave Insurance Fund where employees and employers would be required to contribute a portion of a worker’s wages every week. The contribution cannot exceed 1% of a worker’s total wages.

One provision clarifies that businesses with fewer than 15 employees would not have to contribute to the fund, while all employees, regardless of the size of the business, must pay their share of the contribution.

The bill would allow self-employed workers to participate in the program voluntarily.

Hayes and Valderrama’s bill proposes a contribution of 0.67% of a worker’s wage that may not exceed 0.75% of an employee wage every week. The bill mandates all employees and employers contribute to the fund.

The legislation still faces opposition from some businesses, which opposed it last year.

Representatives for the state’s businesses, including the Maryland Chamber of Commerce and the Maryland Retailers Association, said this legislation represents an untenable financial cost for small businesses trying to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This is not a good time for this,” Mary D. Kane, president of the Maryland Chamber of Commerce, said in an interview with Capital News Service.

Supporters, like Regan Vaughan, advocacy director for Catholic Charities of Baltimore, told lawmakers during hearings that families desperately need help when illness or other issues will not allow them to work, and it would also help small businesses.

“This bill could help the small business owner who feels helpless to financially support an employee who has had to take time during her battle with cancer,” Vaughan said at the hearing. “This bill could help a mom who recently had to hide in a storage closet at her place of employment to participate in family therapy with her child, who was hospitalized for psychiatric reasons.”

Under the bill sponsored by Hayes and Valderrama, a Maryland worker earning an average weekly wage of around $1,080 would contribute $3.62 per week, Hayes said during the hearing in the Senate Finance Committee in early February.

As proposed, the Maryland Department of Labor would collect the money and approve paid leave once an employee submits a claim. Starting the program would cost the state around $21 million, but Wilson said during his committee’s hearing it would not be borne by the state, because the money will be paid back once the fund becomes self-sustaining from the contributions, which would start next year.

The Howard County Chamber of Commerce also opposes the bill as written, spokesperson Christopher Costello said.

Costello said the measure should make it clear that workers cannot take more than 12 weeks of total leave, and that the state insurance would run concurrently with the federal unpaid leave.

Bruce Spencer, the owner of an auto repair shop in Anne Arundel County, also testified against the bill during hearings in the House and Senate committees. Spencer said the biggest issue for him and businesses like his is not paying a percentage of his employees’ salary every week, but finding skilled workers to replace them temporarily.

“We build our labor as a revenue source,” Spencer told legislators. “We have four technicians. You take one out, that is 25% less revenue. The thought of a temporary workforce in a very skilled position is almost nonexistent.”

Matthew Weaver, manager of a Zeke’s Coffee shop in Baltimore, told legislators he needs surgery that will mean taking several weeks off to recover this summer. Although the company wants to financially support him while he is out, it will not be able to bear the cost alone, he said. (Joe Ryan/Capital News Service)

Matthew Weaver, 43, of Baltimore, knows what it is like to be out of work for a severe medical condition and not have financial support.

During hearings, Weaver told lawmakers he went into debt and was evicted twice when he was unemployed for long periods following surgery three years ago and recovery for ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease.

He is now a manager at a Baltimore Zeke’s Coffee shop, a company that supports paid family and medical leave, and he is expecting a second surgery that will require him to take several weeks off to recover this summer.

Although the company wants to support him while he is off work, the owner will not be able to bear the cost alone, he said.

“There’s no way that (the owner) could afford to pay me while I’m not working.”