Gov-elect Wes Moore, D, has a laundry list of plans for Maryland.

Moore wants to give students an option to complete a year of service after high school, raise the minimum wage to $15 this year instead of the scheduled increase in 2025 and support small businesses through modernizing the regulation process.

One of his focuses, which he discussed repeatedly during his campaign, is to provide free pre-kindergarten for all of the state’s three- and four- year olds in need.

The state’s Blueprint Plan promises to expand free pre-K to all children in need in the next 10 years. Passed in 2021 and beginning in 2023, the plan promises to increase education funding by $3.8 billion each year for the next 10 years.

Moore says it needs to happen sooner.

“Our children cannot wait 10-plus years for the plan’s full implementation,” Moore said in his ‘Cradle to Career’ education plan on his website.

Many states, including Maryland, have already launched programs or are in the process of doing so.

Experts and academicians say there are numerous benefits to expanding pre-K access.

“Universal programs are the only ones that ensure all children, especially the most disadvantaged, actually access quality programs,” said Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, an organization considered the lead expert on early childhood education.

“Many children not in poverty gain from pre-K as well, even if they gain less than those who are more disadvantaged.”

Doug Lent is communications director for the Maryland Family Network, a non-profit that advocates for quality childcare for children from birth to age five.

Lent said expanded pre-K would provide families with two benefits while also reducing societal poverty.

“It would give parents access to childcare who could not normally afford that childcare, which means parents can go to work while kids are…also receiving the skills that they need to then later on go into the workforce or into education,” he said.

In Baltimore City, free pre-K builds on the teaching relationship between parents and their children, said Crystal Francis, director of Early Learning for Baltimore City schools.

“Our parents are a child’s first teacher,” Francis said. “So we always want to make sure that we are just kind of opening up and sharing experiences that our kids are having, and supporting families with what they can do at home. You know, we don’t want families to feel like they are not a part of the learning that happens here.”

Experts say pre-K is important because by age five, 90% of the brain is developed.

“It’s not a hyperbole to say that it is one of the most important decisions that a parent will ever make for their child,” Lent said. “The first five years of a child’s life quite literally set the stage for everything that comes after.”

Before the day begins, Dewdney talks with a student, part of a process in which the class can be found playing with blocks and speaking with peers.(Shannon Clark/Capital News Service)

Berol Dewdney teaches pre-K at Commodore John Rogers Elementary and Middle School in Baltimore. Dewdney is also the 2022-2023 Maryland teacher of the year.

On a sunny, but cold Tuesday morning, Dewdney’s students start their day reciting affirmations, some greet her with a hug and all commit to help keep the classroom safe before learning begins. A fall-themed countdown timer plays in the background and helps students learn time management as they play with blocks and toys while their teacher finishes setting up for the day.

Dewdney said she focuses her classroom on brain-based learning – learning that teaches children to plan, focus attention, juggle multiple tasks and to memorize.

Students in the classroom can be seen moving between small groups, creating play plans and putting those plans into motion by using toys set up in the classroom.

“Play is often thought of as this sort of cute thing, but it’s not just cute,” Dewdney said. “It’s powerful. It’s the language of kids, and they are the experts. So, we believe in using a play-based curriculum.”

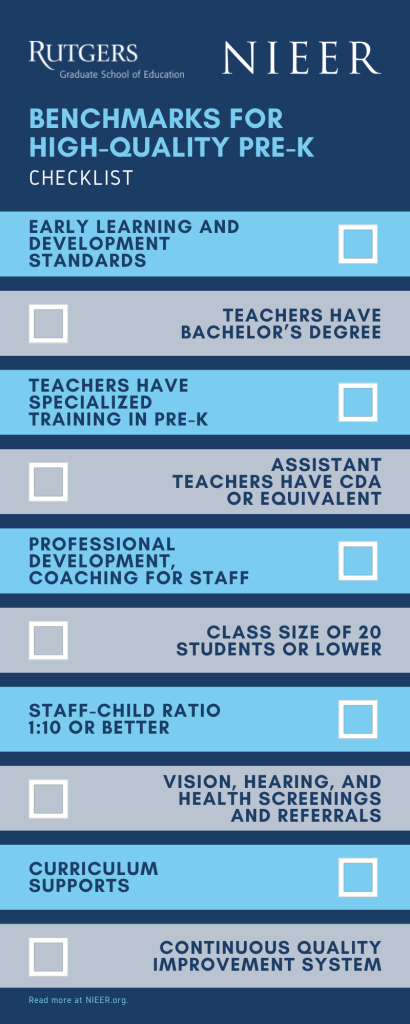

The National Institute for Early Education Research’s ten standards for high quality pre-Kindergarten. (Courtesy of the National Institute for Early Education Research)

Dewdney said she has seen the benefit of having accessible pre-K transcend beyond the classroom.

“Students love learning,” she said. “They love coming to school, but they feel empowered to take that learning wherever they go.”

But the primary question regarding expanded pre-K for Moore and state legislators will be the issue of cost and how to pay for it.

Lent said there is no simple answer to estimating the cost of implementing universal pre-K, due to different factors on how to pay for it.

As of last September, 27,767 students were enrolled in free pre-K in Maryland. In 2021, Maryland spent over $7,414 on each child enrolled, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research.

Georgia became the first state to launch universal free pre-K. It started as a pilot program in 1992. It provides free voluntary pre-K to all of the state’s four-year-olds.

Around 72,000 children are currently enrolled, according to Susan Adams, deputy commissioner for pre-K and Institutional Support for the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning.

During a typical day, Georgia pre-kindergarteners can be found participating in small group activities, playing with other children outside or learning in a classroom setting, Adams said.

The program has multiple benefits, she said.

“You’re going to get families that are going to benefit from it because we have an enriching environment for children to participate in while they go to work or school,” she said.

Every state but Idaho, Montana, New Hampshire and South Dakota have some form of free pre-K, either in development or operation, according to a NIEER 2021 research study. Wyoming and Indiana were also listed, but Indiana now offers grants to low-income families to pay for pre-K and a rural preschool in Wyoming in April 2022 received a community foundation grant for free classes.

Some states like Georgia, rely on the state’s lottery to fund their pre-K programs. Georgia’s program received $400 million for the 2022-2023 school year from the state’s lottery, Adams said, an amount equivalent to the pre-K budget.

Alabama’s First Class Pre-K program is funded through the state’s education budget, which this year allocated around $174 million towards the program, said Barbara J. Cooper, secretary of the Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education.

Moore has said he will pay for Maryland’s expanded pre-K program through taxes on revenue from “cannabis, sports betting and record income tax revenue.” Additionally, he said, he would use money in “capital from the American Rescue Plan and the infrastructure bill,” two federal programs Congress passed last year to help states with a variety of projects.

Implementing free pre-K comes with a suggested list of national standards by NIEER that school systems have adopted as a trademark of a high quality program. Cooper in Alabama proudly proclaims that her state’s program has met the standards for the last 16 years.

The institute’s guidelines include requiring all pre-K teachers to have a bachelor’s degree, classes be capped at 20 students and schools have a “comprehensive, aligned, supported and culturally sensitive curriculum.”

Bowie, Maryland, has a free pre-K program that it launched in 2020 after receiving a $400,000 grant from the state education department. The program, which continues to be state-funded, started at Reid Temple Christian Academy for children in Prince George’s County, which already had a private pre-K program.

Brenda Bethea, interim head of school, said Reid Temple applied to host the program at the request of the city’s mayor, Tim Adams.

“(The city was) very interested in seeing the same results that all of our children here at the academy show at any given time,” Bethea said.

The academy’s private and free programs represent the challenge for Moore and state educators as they expand the state’s existing program.

Bethea said she feels the state-financed program’s curriculum is inferior to that of the school’s tuition-based program.

The tuition-based program uses Wonders curriculum, along with additional resources to “move children forward” developmentally, Bethea said.

The free program has many of the NIEER requirements, all teachers must be state-certified, the program must use state prescribed curriculum and 20 spots are allotted per classroom.

Its teachers use Connect4Learning, a curriculum that Bethea calls a “watered down early childhood program.”

“It is mediocre,” she said. “It is much needed, but it is a mediocre product that has been offered to children.”

Back in Baltimore, Dewdney advises state officials to be mindful as they implement the expanded program.

“It’s a very pivotal moment in Maryland, but also in our country,” she said. “There’s a lot of energy around pre-K, but there is a difference between honoring and knowing that early childhood and high quality early childhood education matters and making that happen.”