In one of the most consequential bills of the 2023 session, the General Assembly approved the first major changes to the Forest Conservation Act since it was enacted in 1991.

The 2023 Forest Preservation and Retention Act (SB 526/HB 723) will require developers and local governments to abide by more stringent forest conservation standards. The changes revise forest preservation and mitigation requirements, restore the use of forest retention banking and provide alternatives to replanting trees in growth areas that recognize the value of forest quality and make the law align better with current development and redevelopment patterns.

Maryland’s 1991 Forest Conservation Act was the first state-wide law in the country to regulate the clearing of forest during land development. It was complicated and controversial but deployed an ingenious sliding scale of replanting requirements and forest conservation thresholds that resulted in the retention of trees on forested sites and the strategic planting of new forest where none existed. The approach was seen as complex and burdensome by some, unfairly lenient by others, but it allowed land zoned for development to achieve density while reducing the clearing of forest.

Maryland’s 1991 Forest Conservation Act was the first state-wide law in the country to regulate the clearing of forest during land development. It was complicated and controversial but deployed an ingenious sliding scale of replanting requirements and forest conservation thresholds that resulted in the retention of trees on forested sites and the strategic planting of new forest where none existed. The approach was seen as complex and burdensome by some, unfairly lenient by others, but it allowed land zoned for development to achieve density while reducing the clearing of forest.

The changes come at the end of a six-year-long debate where diligent work by a forest conservation workgroup comprised of NAIOP and Maryland Building Industry Association (MBIA) members and staff helped prevent the passage of bills that would have drastically reduced development potential in growth areas.

Beginning in 2017, environmental and community groups cited “unsustainable deforestation” from development and urged the legislature to make sweeping changes to the act. A series of bills proposed sharply increased mitigation requirements, a broader definition of priority forest, approval of a variance before clearing priority forest and limitations to off-site forest mitigation banking.

Lack of clear data on the impacts of development activity on state-wide forest cover and disagreements over how to balance the parallel goals of forest conservation and growth-area density resulted in the General Assembly killing overzealous bills and heavily amending other legislative proposals to make them either task force reports or technical studies.

In 2019, the Assembly commissioned the Harry Hughes Center for Agroecology to complete a comprehensive study of forest and tree canopy.

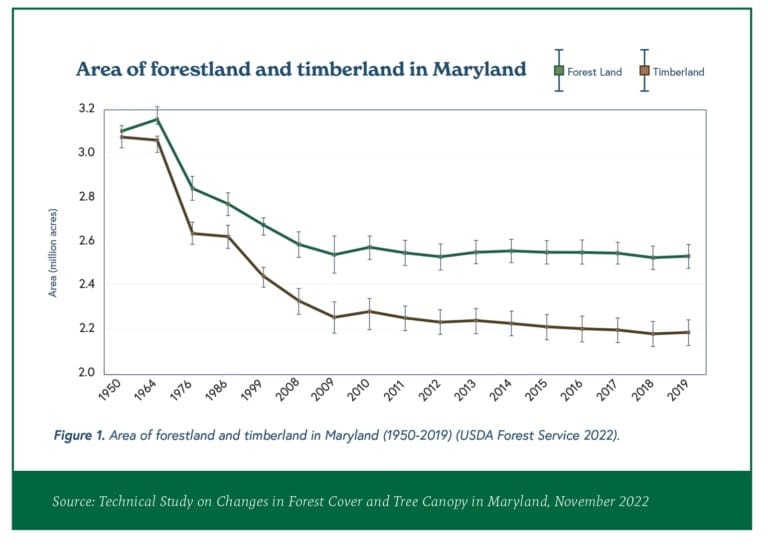

Released last October, the study found that since 2009 Maryland’s forest and tree canopy cover declined but stabilized in recent years. Between 2013 and 2018 total tree canopy decreased annually by 0.077% per year – a remarkable, “stable state” given that Maryland’s population grew by more than 880,000 people or 17% during that period.

Forest converted to development uses amounted to 52% of the change over the study period.

The 2023 act initially proposed mitigation requirements fourfold higher than the existing law for non-priority forest and eightfold higher for the clearing of broadly redefined priority forest. For heavily forested sites, that math simply did not work. General Assembly leaders reduced the proposed mitigation ratios by half in the final version of the bill.

For development sites within Priority Funding Areas, the bill increases mitigation requirements for non-priority forest from the current quarter acre to a half acre for each acre cleared. Clearing priority forest is mitigated on a 1:1 versus the 2:1 ratio in the original bill. Exemptions for development in Transit Oriented Development Zones and multifamily housing lower mitigation ratios below current law to a half acre of forest preserved offsite for each acre cleared.

The final bill narrowed the definition of priority forest and requires design teams to make “best efforts to avoid” clearing but does not require them to obtain an administrative variance from the local government.

Other counterbalancing changes were included in the final bill. Existing forest conservation thresholds and their 2:1 mitigation penalty for clearing below minimum levels were not retained in the new law. Planting street trees was retained and restoration of degraded forest was added as mitigation measures for projects located in growth areas.

“This is a big change in forest conservation in Maryland, but NAIOP members need to realize that we had big wins in amending this bill,” said Matthew Wessel, Senior Director of Rodgers Consulting. “MBIA and NAIOP were the only groups opposing the bill for the last two and a half weeks of the session and building support for compromises.”

One influential trade-off was the inclusion of a provision requiring developments with unforested stream buffers, to reforest those areas.

“That’s a win-win compromise. You get the most environmental bang for your buck in terms of clean water and meeting the state’s goal of increasing the amount of forested stream, riparian buffer,” Wessel said. “It costs a little extra, but it doesn’t eat into developable area, and it helped convince the General Assembly to back off of excessive mitigation ratios.”

Negotiations resulted in the continuation of forest retention banking in Maryland. Although developers and local governments have used forest banks created by preserving existing forest for 20 years, the legislature previously passed legislation to terminate the practice within the next two years.

The final version reinstates the use of forest retention banks for up to 60 percent of offsite mitigation. Forest mitigation banks based on planting of new forest can be used for up to 100 percent of offsite mitigation.

“The provision is not as good as it has been for the last 20 years… but it’s better than nothing,” Wessel said. “It helps developments go forward and it incentivizes people to preserve existing, large, mature tracks of forest which the state rightfully says are very important.”

Finally, the bill establishes a new state-wide goal of net gains in forest and tree canopy acreage. The significance of this change might be felt most in Prince George’s, Calvert, Harford and other counties that have high levels of existing forest cover on land zoned for development.

It remains to be seen whether the 2023 law will be workable or if further changes will be necessary to balance the state’s environmental protection and growth management objectives.

“The biggest impact the bill creates is it pushes the state very quickly towards a no net loss of forest to development,” said Kevin Haines, Founder of Holly Oak Consulting.

Although the goal to increase forest and tree canopy acreage will be measured state-wide, the bill’s impact on development projects will vary depending on location.

It requires local jurisdictions to comply with the forest conservation requirements or demonstrate that their own regulations have resulted in no net loss of forest to development over a four-year period. Some jurisdictions – including Anne Arundel, Frederick, Howard and Montgomery counties – have already passed forest conservation legislation similar to or more protective than the state bill.

Other jurisdictions, like Baltimore City and Carroll County, have already cleared large portions of forest, leaving little forest that could be impacted by development. Some rapidly developing counties – including Harford, Cecil and Prince George’s – have not significantly updated their forest conservation requirements since the 1991 state law was passed.

“It takes a lot of effort to craft that type of legislation. For a county like Harford, it’s going to be a heavy lift and I could see them defaulting to the state law,” Haines said. “Consequently, they are going to have higher mitigation requirements, higher in lieu fees and there will be more approvals that developments need to get through. It is going to slow things down for a while as everyone figures out how to deal with this change in the law. “