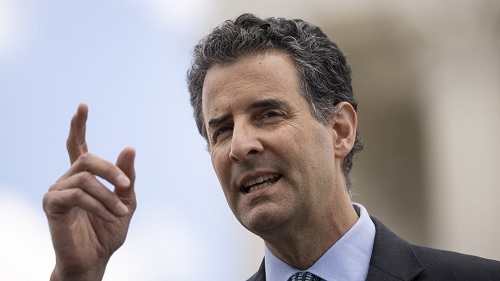

U.S. Rep. John Sarbanes (D-3rd) was standing in the back of a room on Capitol Hill amid a cramped maze of office carrels the other day, fruitlessly fiddling with the volume on a big-screen TV.

The final weeks for a retiring member of Congress may involve glowing tributes from grateful constituents, colleagues and interest groups. But when it comes to the work environment, dignity is in short supply.

Departing members have to be out of their Capitol Hill offices by Thanksgiving, and this was Sarbanes’ temporary digs in the Rayburn House Office Building. It was last Friday, the day the House of Representatives would finally adopt a temporary spending plan to avoid a government shutdown, and Sarbanes was hanging around, packing up and waiting to cast his final votes as a member of Congress.

“Am I surprised we’re having this last-minute showdown?” Sarbanes mused. “Not particularly, given the crowd we’re dealing with. But it’s pretty outrageous.”

Sarbanes, 62, a soft-spoken, workman-like and cerebral presence in Congress, like his father, the late U.S. Sen. Paul Sarbanes (D-Md.), is departing after 18 years representing central Maryland in the U.S. House. That’s a fairly young age for a congressional retiree, and Sarbanes is looking forward to the next chapter of his professional life, even though he doesn’t quite know what it will look like.

Over the past two decades, no member of the House has been a more resolute defender of the Chesapeake Bay than Sarbanes, whose district currently includes a large swath of Anne Arundel County.

“Congressman John Sarbanes has been an absolute warrior for the Bay,” Gov. Wes Moore (D) said during a meeting of the Chesapeake Bay Executive Council in mid-December. “It wasn’t just during his time in Congress, but before that.”

Sarbanes has also been associated with legislative efforts to boost health care protections, and mental and behavioral health programs, and has been a champion of consumer rights and public employees.

But his true legislative legacy is around the issues of political reform, civic engagement and democracy; for the past few Congresses, the Marylander has been the chief sponsor of legislation to expand voting rights and limit the influence of big money on politics — which House Democrats continue to make a top priority, even as the measure has stalled at various stages of the legislative process. That push has dovetailed with an increasing number of voters’ dissatisfaction with what Sarbanes calls “big fill-in-the-blank — big PhRMA, big tech, big [agriculture].”

But the failure of the legislation to become law so far is also a reminder of how powerful and big-moneyed special interests still control the political process, especially in Washington, D.C. And Democrats, Sarbanes believes, lost the 2024 election in part because they didn’t do enough to skillfully and vocally broadcast their commitment to helping everyday people over corporate interests.

“The great irony in this is that Donald Trump seemed to come at people with that kind of message,” he said. “The irony is that he’s one of the most corrupt individuals by any measure.”

Sarbanes believes that the incoming Trump administration, with the president-elect’s affinity for billionaires, will help the Democrats politically and help the political reform movement generally.

“There will be opportunities for us to highlight and crystalize that, ‘He’s not really for us,’” Sarbanes predicted. “We’ve got to have ideas, proposals, to show voters that we’re on their side…. The average person has got to see that distinction.”

Sarbanes plans to continue to promote for political reform and civic engagement as a private citizen. He envisions affiliating first with a university and possibly landing eventually with an advocacy or good government group.

“I’m leaving Congress — I’m not walking away from the work,” Sarbanes said. “Looking back over these 18 years, all these partners I’ve been working with, they’re not going anywhere. I’ve always been able to take something I’ve done before and pulled it into the next thing.”

Asked whether he’s excited or scared to have to figure out what’s next, the congressman smiled and shifted in his seat.

“Both,” he replied.

Hopes and fears

Sarbanes concedes that he’s worried about the future of the country with Trump returning to power. He’s worried about national security — including the future of U.S. relations with Greece, his family’s original homeland, with Trump’s intention to nominate Kimberly Guilfoyle, his son’s pugilistic fiancee, as ambassador to Greece.

He’s also worried about the conservative drift of public policy and fears that Trump and his political allies will chip away at basic freedoms.

Sarbanes believes the second Trump term will be different from the first, and is thankful that Trump won’t have successive terms. He also believes the opposition to Trump will be different this time. Trump foes, he argues, will need to focus on the damage he may do over the next four years rather than daily doses of outrage, and figure out how to repair vital institutions when Trump leaves office — if in fact they can fixed.

“I’m using as my ‘R’ word resilience more than resistance,” Sarbanes said. “We need to look for opportunities to nurture and fortify that.”

Fueling Sarbanes’ cautious optimism are the four new members set to join Maryland’s congressional delegation, including three — Sen.-elect Angela Alsobrooks (D) and Reps.-elect April McClain Delaney (D-6th) and Sarah K. Elfreth (D-3rd) — who will become the first women in the delegation in eight years. They’ll all be sworn in on Jan. 3, when Sarbanes’ term ends.

“The Maryland delegation is getting to look a lot more like the state,” he observed.

Sarbanes heaped praise on Elfreth, a 36-year-old state senator who won a 22-candidate primary to replace him earlier this year. Sarbanes describes heras a savvy, hard worker who will serve their constituents well. He has advised her that coming from the General Assembly, where she quickly passed several policy initiatives, she’s got to prepare for the slower and less congenial pace of Congress, and should initially focus on constituent work and forging bonds with colleagues.

“It’s a tough transition for people who come from legislatures, where you start a session with an agenda and you get it done,” Sarbanes said.

Elfreth paid tribute to her predecessor in a recent email message to supporters.

“As Rep. Sarbanes passes the baton, I’m honored to carry his legacy forward and continue his important work to reform and strengthen our democratic institutions, our natural world, and our people,” she wrote.

To put a capstone on his time in Congress, Sarbanes is celebrating the passage of legislation in the final weeks of this term that he worked on with departing U.S. Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.) and Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D-7th) — friends of his father’s. The bill names the visitors center at Fort McHenry in Baltimore after the elder Sarbanes, who secured the funding to rebuild it years ago, ahead of the War of 1812 bicentennial.

The push to name the visitors center after Paul Sarbanes dates back to when he was still alive, but in his typically modest fashion, he rejected the idea, his son recalled.

“I thought, ‘He’s not here to stop us this time out, so we can get it done,’” he said.